Giardini d'acqua Porto Cesareo

"Memory is a truly strange tool, one that can bring things back, like the sea that returns scraps of a shipwreck, even after many years."

Primo Levi

Like grains of sand falling in an hourglass that mark the passing of time but do not disappear, so, too, the past reveals itself here in layers, in this strip of land eaten away by the sea. It is here between the ruins of ancient watchtowers, massive boulders launched by tsunamis from the sea in the distant past, and traces of long lost villages. Reading these clues left by history, the path to our current moment is that much clearer.

A Prehistoric Village

In 1978 the archaeologist Salvatore Bianco began research in the area near Torre Castiglione, bringing to light stone utensils that can be dated to the late Bronze Age, revealing the existence in situ of a prehistoric village. Unfortunately, the construction of the tower itself disturbed nearly all of the archaeological evidence, which was already deteriorated considerably by erosion from sea water. The presence of some ceramic artifacts from medieval times and later periods confirmed that the site had been frequented by man in a more or less constant manner over the centuries.

“The fact that prehistoric materials can be linked to an actual village is proven by the presence of plaster fragments from huts, in part bearing the imprint of the wooden frame of the hut itself. In addition, there are three bowl fragments in quartzite and a limestone flour mill of a large size with an irregular oval margin; this bears witness to the developments reached in agriculture during the Late Bronze Age.” (S. Bianco, Torre Castiglione: insediamento proto-villanoviano. Ricerche e studi, Brindisi. 1978).

The huts had a single room, either circular, oval or rectangular in form. The walls, made up of plant-based elements held together by a series of wooden blades, were covered on the inside and outside with a thick “plaster” made from pressed clay. The pavement was in beaten clay, while the studded walls supported the roof that was made of beams covered in plant material. The outside door was reinforced by two poles placed in an X, creating a small portico.

Torre Castiglione

The construction of watchtowers along the coast of Apulia, from the Byzantine era until the reign of the Normans, came about to defend the coastline and the hinterland from Saracen invasions. Torre Castiglione is part of a system of coastal watchtowers financed by the Spanish Viceroys of Naples, meant to protect the Terra d’Otranto (Otranto territory).

The construction of the tower named the Ponte de Castiglione, dates back to 1568. The contract for the construction was assigned to Virgilio Pugliese, a master builder from nearby Nardò, who was tasked to follow the design of the engineer Giovanni Tommaso Scala and complete it within nine months time. Following the death of Pugliese, the work was completed by another builder from Nardò, Leonardo Spalletta. Recorded as being in a good state in 1825 by Primaldo Coco, the tower was still in use by the Guardia Doganale (customs guard) in 1842. In 1972 it was listed as a ruin, and its collapse was likely caused by a cave-in of karstic origin. Today, in the pile of rubble that remains there are still at least a dozen square meters of original pavement and traces of what was likely a well.

Detail sheets

A System of Defensive Towers

San San Pancrazio Salentino – Church of Saint Anthony of Padova – a fresco of the assault of 1547 (Photo credit: http://www.brindisiweb.it)

The architectural design, systems of communication and the locations of towers along the coast, often on high ground or very close to the rocky coastline, makes it evident that these buildings were not conceived as a means for assaulting an enemy, but rather to defend territory and the local population. The towers had to include a rampart/embankment at the base to defend against firearms, while on the ground floor, generally, there was shelter for animals. The life of the squadron, made up of torrieri (tower soldiers, who were required to pass a dedicated exam and relative license), cavallari (cavalry), and three or four armigeri (arms specialists), took place in the upper floors and the crows nest at the summit of the tower. Once the enemy was sighted, the guards could warn the local population on horseback (cavallari), or at a distance by using smoke signals. These were created by burning bales of straw and heather damp with water and bitumen, and using an iron basket to run on antenna of sorts. They also used fires called “fani,” gunpowder stockpiled for firearms, banner waving, sounds generated by dedicated instruments like the buccina (nautical trumpet) created using a conch shell, or even, in some cases, the use of carrier pigeons.

“The people destined to guard these towers during the night are obliged to warn the nearest city with as many fires as there are ships sighted that day. Then, the tower that lies nearest responds with just as many fires, warning the next, and so on, and so forth, as each warns the next.” Antonino Mongitore (1663 – 1742) historian and author

source: www.anticabibliotecacoriglianorossano.it

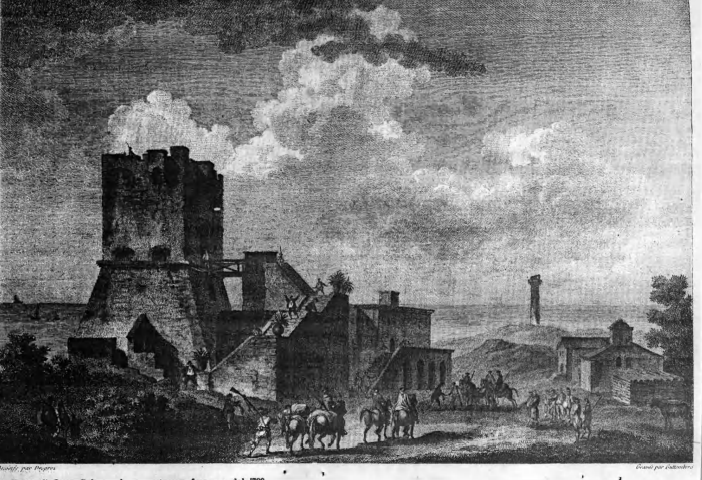

Engraving by Guttemberg from which it is possible to study the stair structure communicating with the tower by means of a wooden drawbridge.

Watchtower Types

For the construction of the towers, local stone like tufo, volcanic tuff stone, or the harder and more resistant càrparo, a sedimentary calcarenite, were used exclusively (De Giorgi, 1981). The very first watchtowers from the 14th and 15th centuries were built on circular plans, and it is only in the 16th century that they were elevated onto quadrangular bases, whose resulting corners could be exploited for artillery storage. Initially they had no external stairs, accessible instead by cord ladders built with wooden steps, that permitted entry into and exit out of the towers. Such structures were built with two communicating floors.

From analysis of the coastal towers in the Province of Lecce, there appear to be five principal types:

The five tower types from the Terra d’Otranto and their relative sizes: I. Square-based tower typical of the Kingdom of Naples; II. large square-based tower (from the Nardò series); III. Large and medium circular-based towers; IV. Small circular-based tower (from the Otranto series); V. Octagonal-based tower a cappello di prete, “like a priest’s hat” as these star-shaped constructions are locally known. (Source: F. Bruno, V. Faglia, G. Losso, A. Manuele, 1978, p. 55)

Torre Castiglione was initially indicated by Vittorio Faglia in 1978 as belonging to the Nardò series (v. type II from above), however more recent studies by F. Errivo attribute them “clearly, and unequivocally […] to the series of towers typical of the Regno [di Napoli],” (Errico, 2018), or type I as listed above. In the Censimento delle torri costiere nella Provincia di Terra d’Otranto, Torre Castiglione is listed with a base measuring 11 meters per side, while its walls seem to have a thickness of 2.5 meters. (F. Bruno V. Faglia G. Losso A. Manuele, Censimento delle torri costiere nella Provincia di Terra d’Otranto – Indagine per il ricupero del territorio, Istituto Italiano dei Castelli, Rome, 1978)

Example of a tower “typical of the Kingdom of Naples,” Torre San Giovanni della Pedata in Gallipoli

(source: www.bpp.it)

Maciniello and the Cavallari

Nearly 900 meters east of the ruins of Torre Castiglione there is a building called the “Maciniello,” currently under restoration in the project to valorize the spunnulate. Built using a rubble stone filling technique, it appears to have a roof structure with a barrel vault and an arched entryway on the northern side, which faces the sea. On the eastern side the building extends into a dry stone wall in the surrounding field. From the point of view of topography, the building is equidistant from the two nearest towers, which is the precise reason that they are referred to as torri speculari, or mirror towers. It is also located just a few dozen meters from the rocky coast. It is known locally as Macinieddru or “lu puestu” (headquarters). The latter is probably related to the names given to the small homes of cavallari along the Calabrian coast such as: Posto di Capo Bruzzano, Posto di Guardia di Pigliàno, Posto i Palazzi, among others.

Detail sheets

The Maciniello - toponym

Notorial cartouche from 1777 (Lecce State Archives)

The first reference to a “logo Macin(i)ello” or “place of Macinello” can be found in a notorial act within a 1777 cartouche, held in the collection of the Lecce State Archives, where, in the presence of the notary Francesco Saverio Trotta,

“Domenico D’Amato da terra di Veglie […] cavallaro di logo di Maciniello [e] Donato Varniola di Veglie cavallaro di logo di Macinello, […] non con forza, dolo o inganno alcuno, di loro libera e spontanea volontà, con giuramento attestano, confermano e dichiarano…[etc].

“Domenico D’Amato from the land of Veglie […] cavallaro in the place of Maciniello [and] Donato Varniola from Veglie, cavallaro in the place of Maciniello, […] without any force, malice or deceit, of their own free and spontaneous will, with an oath attest, confirm and declare…[etc]”

As is clear from the text above, in this case it is referred to not as a puestu, but rather as a logo.

Details of the notorial act (Archivio di Stato di Lecce)

The Maciniello - intended use

In his 1989 publication “Maritime Towers of the Terre d’Otranto,” Giovanni Cosi confirms that “between two towers there were often villages overseen by cavalry (cavallari).”

Calabria Ulteriore (L. Ruel, 1784-1786) (fonte: www.academia.edu)

For more detailed references about the use of this ancient structure, built between two towers, one must take a look at the “Nuova carta geografica della Calabria Ulteriore,” by the military engineer Luigi Rue, mapping the southern tip of Calabria. In these maps the watchtowers appear separated by a series of quadrangular marks, which spread out along the entire perimeter of the area. These marks correspond with building designated for housing the personnel in charge of supervising the coast, which were formed by cavalry, tower foot soldiers (pedoni torrieri), and others.

“The houses of the cavallari were equipped with stalls[…] and were located at regular intervals […] Each house was 30 palms long, 16 wide and 14 high, with an attached manger for two horses and partitioning for the storage of hay.”

(Vincenzo Cataldo, Le casette dei cavallari nel sistema integrato di difesa costiera nel Regno di Napoli, 2016).

Cavallari House (State Archives of Naples)

When this little house, in particular, was rebuilt over the previously collapsed building, it was designed to house not only the cavallaro and his horse, but also those brought in after being saved from shipwrecks, a frequent occurrence.

(source: www.academia.edu)

The cavallari

The unpredictability of events in some historical periods and reduced viability of these towers at night required the integration of a further surveillance service to provide the night alarm, when these posts had their most crucial role in the territorial security apparatus. Every tower was therefore assigned a caporale (corporal), nearly always Spanish and nominated directly by the Viceroy, a torriero, and a number of cavallari proportionate to the strategic importance of that particular post.

Once a threat had been ascertained, the torriero made sure to activate the tower’s systems of communication, albeit fire, smoke, or the more rapid acoustic signals and artillery when on hand. As soon as the tower watch gave the signal, the cavalry, took to their mounts and traveled among the internal towns and villages to quickly spread the word about the imminent danger.

“Mariano de Falco dell’Avetran, cavalryman in the Castiglione guard, on September the 11th 1567, received 8 ducats for service rendered during the months of July and August 1567. Palmerio Scardino di Maruggi, cavalryman in the port of Salice in the area called Castiglione, on the 13th of October 1567 received 4 ducats for services rendered during the month of September. Mariano de falco, cavalryman as above, on October the 22nd 1567 received 4 ducats for services rendered during the month of September.”

(G. Cosi, Torri marittime di Terra d’Otranto, 1996)

The cavallari served for three years and were organized into “ordinary” and “extraordinary” divisions that were overseen by a sopravallaro, who did not take an active part in sounding the alarm. The soldiers worked primarily during the spring and summer months, as these were the most favorable for sea navigation. Often these cavalry were poorly paid, and rarely on time. This, in addition to their posting in isolated and grueling conditions, contributed to the fact that they rarely did their duties to the fullest extent. It was even common for cavalrymen to abandon their posts or even to make pacts with pirate invaders.